Jack Evans Doth Protest Too Much

2009 Recusal Anything But Ethical

Published at HillRag

In an attempt to hold onto the seat that he has held on to for nearly 30 years, Ward 2 Councilmember Jack Evans (D) is fighting accusations of corruption.

In September, Council investigators questioned Evans four separate times, never under oath. Throughout the interviews, Evans surprisingly referred back to his 2009 recusal as an ethical high-water mark.

“Do you have a rule of thumb with regard to how you assess whether there’s an appearance [of a conflict of interest]?” the lead Council investigator asked Evans, who replied: “Best example of that, I think it goes back to the Marriott situation where there was no conflict. The public believed there was even though there wasn’t and I recused myself.”

The “Marriott situation,” in my view, actually demonstrates Evans’ lack of ethics.

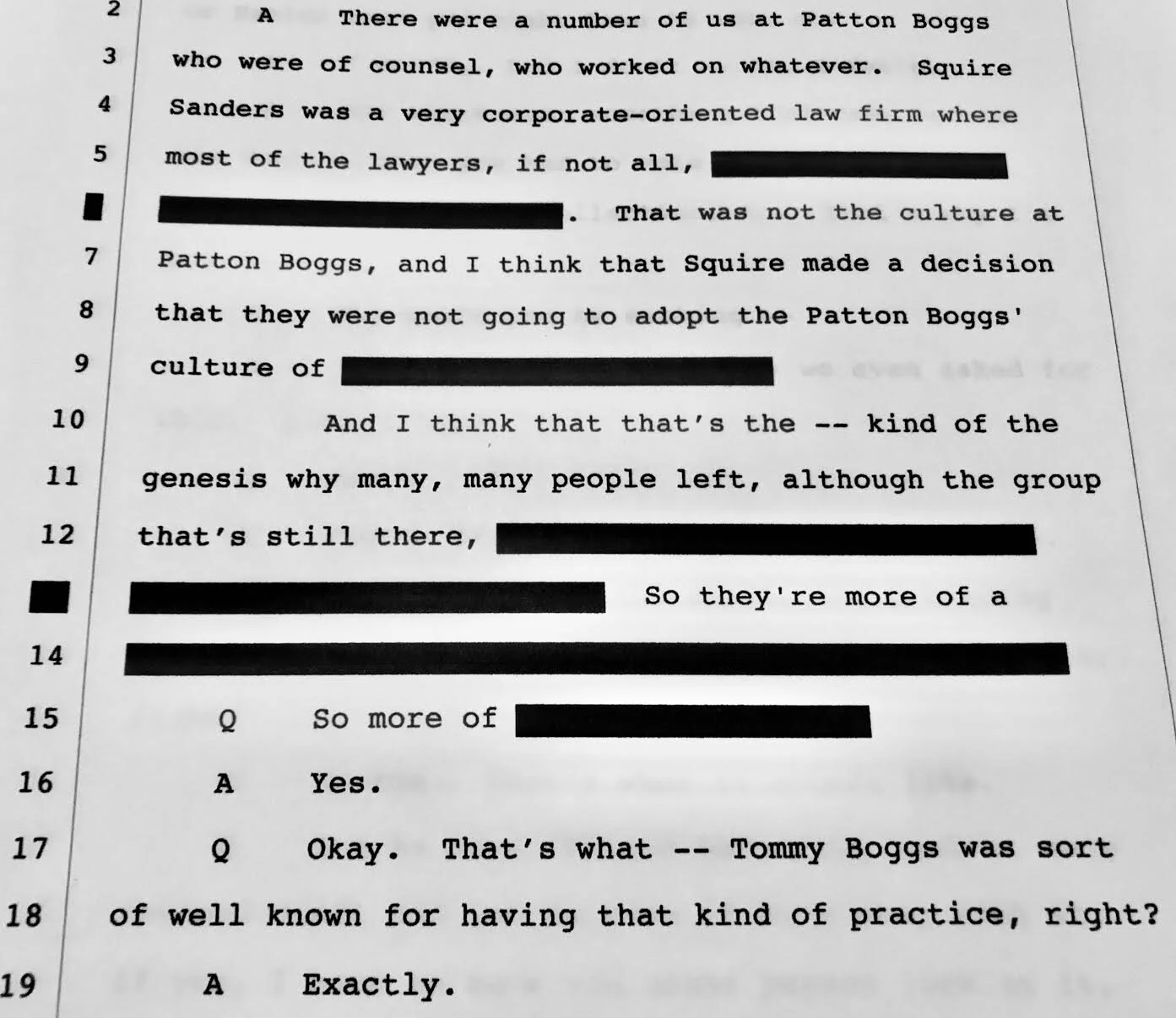

In 2009, the Council approved a deal providing $272 million in public money to assist Marriott in building a nearly 1,200-room hotel alongside the convention center. At the time Evans was chairman of the council’s powerful finance and revenue committee. He was simultaneously on the payroll of Patton Boggs, a lobbying powerhouse, which garnered him an additional $190,000 a year on top of his $125,000 council salary.

The hotel deal had just one public hearing. Evans had a starring role in it. While co-chairing the session, he strongly argued for the project. If not for deals like this, “our downtown would probably resemble Detroit,” Evans said, chastising opponents of the proposed massive public subsidy.

When my friend Dave Mallof and I went down to the Wilson Building to testify at this June 2009 hearing, we had a hunch that Evans might have a conflict of interest. The deal had the telltale signs of impropriety that we had learned to spot over the years. Firstly, it involved public land in Evans’ ward and lots of public money. Secondly, it benefitted a Fortune 500 company, Marriott and had Evans’ strong endorsement.

“You need to please just reassure the public that standard conflict of interest checks have been run within Patton Boggs, and that you’ve got no conflicts,” Mallof, then vice president of the Federation of Civic Associations, said in testimony before Evans. The councilmember declined to respond.

Two days later, at a sparsely attended late-Friday afternoon committee meeting, Evans unexpectedly recused himself from voting on the deal. He continued doing so going forward, claiming it was to avoid “any appearance of a conflict of interest.”

The next month, despite civic groups expressing their growing concern, the Council unanimously approved the deal.

However, the project came to an abrupt halt in January 2010. Mega-developer JBG, reportedly angry at Marriott over a separate matter, sued to stop the hotel deal, claiming it was a sole source contract. Marriott and the city countersued. It was a mess.

To get things back on track, Evans quietly reinserted himself, making a mockery of his earlier recusal. Behind closed doors at city hall, Evans and then-DC Attorney General Peter Nickles brought the warring parties together. “What Marriott and JBG agreed to in the deal is not known,” The Washington Post reported. What is known is that after the private meeting the stalled project moved forward.

As debate over the hotel deal swirled again in 2011, Patton Boggs interjected itself, stating Marriott was not a client of the firm. The statement conveniently omitted a crucial detail. The firm represented another major player in the deal.

This fact may never have seen the light of day, if an email from an Evans staffer hadn’t surfaced. The staffer wrote that Evans had recused himself because Patton Boggs “represents ING who are the equity partners in the private financing part of the hotel.”

When questioned by reporters, Evans confirmed that ING was indeed a client of Patton Boggs, but he said this was not a problem. “In my viewpoint, there was no conflict of interest,” Evans told The Washington Post. Even though the city was providing $272 million in public funding, since ING’s agreement was with the developer, ING “had nothing to do with the city,” Evans claimed.

The Washington City Paper found Evans’s argument less than convincing. “When the city and developers go in on a deal together like the convention center [hotel], and Evans has ties to parties on both sides, that seems at the very least like a potential conflict of interest,” it wrote.

DC law requires that councilmembers file a written explanation for their recusals, but Evans never did. When journalist John Hanrahan pointed this out, Evans responded by calling him an “idiot.”

Evans is unlikely to face consequences for lying to Council investigators, since he was not under oath. He will also escape any public reckoning for his role in the 2009 hotel deal, which falls outside the narrow scope of the current federal investigation. Unless the Council expels him, Evans will have made another great escape from the consequences of his ethical lapses.